While it doesn’t make sense commercially to grow all crops fully indoors, there can be a significant plant health and economic reasons to consider propagation of seedlings in a vertical farming environment. The pandemic had significant impacts on supply chains, including food and seedings, exacerbating existing challenges with diseases and pests that come through the transportation and handling of seedlings. Vertical farming presents an opportunity to address some of these issues by propagating quality seedlings in a totally controlled environment to then transfer into poly tunnels or open fields with the comfort of knowing that the quality and health of the plant is intact. The potential this brings for roots, fruits and even trees is significant, and the combination of the science and technology is only really starting to scratch the surface here. To discuss this further, we welcome Archie Gibson from Agrico UK: one of the world’s largest seed potato distributors. Archie is also on the Board of the James Hutton Institute.

What would you highlight as some of the key challenges facing the agriculture and food growing sectors?

The immediate challenges include Brexit and the reality that about 25% of Scotland’s seed markets – which previously centred around countries of the EU – have been denied to us with the EU prohibition on certified seeds from the UK going into Europe. That has been hugely disruptive. COVID-19 has also caused significant disruption with food service and dining out opportunities being seriously interrupted by lockdowns etc.

Cutting back to the hard facts around agriculture, the challenges are plain to see. We have the need to find more stable ways of producing our products competitively, we’ve got climate change and with COP26 coming up these are all factors that weigh heavily on our sector and are a huge concern to us. At the same time, potentially they offer us an opportunity so one should not be all gloom and doom. But you add these together and they make for very challenging times.

We perhaps have been too good at producing safe, affordable food for our population – complemented by the 50% of food stuffs that are imported into the UK – and perhaps we are in a transition time in that regard.

How important is technology in the future of agriculture and food production?

Technologies come and go. There are always some that are disruptive and others that force the hand of change. But one of the things I think is fundamental is long-term soil health to ensure we have a sustainable and resilient industry going forward. This requires focus on how we do things and how we grow plants, where we grow plants and how we manage climate change. Looking at how we can mitigate risk is also an important focus because the moment you put something in a field you are, in a sense, in the hands of the gods.

If you then factor in the aim of regulatory authorities to reduce the amount of chemicals used in crop protection products, then the reality is that we have got to get smarter about what we do and how we do it. Whether that is growing early generation products and seeds in a growth tower (which IGS has been championing); or whether it is nurturing crops through their journey from that stage into the field and focusing on how we keep things healthy in fields.

Can you explain more about the potato production process?

Potatoes are clonal, which is the reason you have consistency of product from one potato crop to the next. Potato cultivars are all looked after by an organisation called Science & Advice for Scottish Agriculture (SASA) and they maintain a library of all the varieties that are commonly grown in the United Kingdom and they ensure that all these little seeding plants are free from all identifiable pests.

These are grown in a laboratory situation,. So when you commission mini tuber production, for example, the farmer will cut from each leaf nodule a tiny micro plant which they will put into a petri dish with agar gel in the bottom. That then grows before it is pricked out of the petri dish and put into a coir plug where it is grown.

From there, growers produce smaller plants from these tiny little plantlets and each throws down its roots and sets perhaps one or two tubers. Each of these tiny little plants – known as field generation zero – start out life in a glasshouse or polytunnel. It takes a whole year cycle before they can go into the field, so in year two they will be planted out alongside a whole lot of other mini tubers. We multiply them over a number of years and each year they get a progressive classification reference. We can do a maximum of seven years’ multiplication and that’s when it is felt that the clone is becoming a little bit tired and are more prone to pick up disease. From about year four onwards, we can sell bulk commercial quantities of seed to growers who produce the potatoes that eventually reach the consumer via supermarkets or convenience stores or through industry varieties that are made into crisps, chips or the many other products that are available.

How long does the breeding cycle take?

The breeding cycle takes a minimum of ten years and that’s when you do the first hybrid crossing between two parent plants which both bring different qualities to the table. We want next generation varieties to have a number of key characteristics which are so important to the future, success and commercial success of the potato sector. So, for example, we try to make sure that they have at least two resistant genes to common blight. Like COVID, blight strains are ever evolving, so you have to have a dual resistance capability within this new cultivar, this new potato. By the time it gets to eight years, we decide if it has got some potential commercially. At that point, it becomes subject to national listing and goes through a two-year review process with the ideal outcome being that it is then classed as a distinct variety with its own set of genes. We try and stack blight resistance with tolerance to certain type of free-living nematodes which are basically micro worms that live in the soil structures: some of them are positive and some are negative. Historically that threat has been overcome with the use of agrochemicals but less and less in this day and age.

What is Agrico’s role?

Agrico does the first ten years to bring forward varieties and then it typically takes about five years to establish market appeal. It is very much about marketing having samples to allow people to observe and evaluate these new varieties to see how they compare against existing varieties. You of course then have to be able to scale up if they are successful: we probably have a success rate of about one in six. It’s a long process and is quite drawn out and expensive: around a million pounds to bring forward a new variety with comprehensive trialling in multiple countries in different growing conditions over the course of ten years.

What challenges are currently facing the seed potato market – both here in UK and internationally?

The market is highly competitive. There are breeders who operate on a much smaller scale – out of their garden shed or greenhouse – that’s not the way we do it at Agrico.

Our operations are very scientific and laboratory-focused, with crossings and back crossings to eliminate negative traits. In our next generation portfolio currently we have ten varieties all with dual blight resistance. That is vital if you’re looking to deliver a potato crop across the world that has genes that protect that plant and allow it to deliver a marketable yield. This means if you are in a temperate zone like sub-Saharan Africa you can grow excellent potatoes that carry blight resistance. For countries that cannot afford crop protection products, that’s the difference between feast or famine. Only in the developed countries of China, North America and Europe is it standard to apply crop protection chemistry.

How might more controlled environmental growing parameters address these challenges?

The key thing in any sort of clonal production system is maintaining high health: the higher the health of the progeny crop, the more success the grower who is growing the consumption crop will have across both yield and quality.

The ultimate challenge for any breeder – which is where Agrico comes in – is to work with growers to produce high quality seed which stores well and subsequently grows well to produce a satisfactory yielding consumption crop.

We are lucky in Scotland as we have a good mix of naturally good soil, and highly-skilled, experienced growers. We are also pretty resilient because potatoes are successfully grown across the country. And if you extend that to a UK level, potatoes are grown literally from Penzance to Thurso: that is a fantastic range. Potato lends itself to the different latitudes across the UK and different areas can focus on slightly different things. For example, early crops in Penzance and possibly into South Pembrokeshire/South Wales, core storage varieties in the Midlands and into Scotland for table potatoes. We have fantastic opportunities.

So where would the vertical farm fit in?

If we go back to the idea of quality, a vertical farm can help. A polytunnel or glasshouse is still subject to a lot of environmental impacts relative to daylight, soil conditions, temperature and water availability, whereas a vertical farm is highly regulated. Our experience working on trials with IGS has been absolutely fascinating and I think for both of us we learnt a great deal from it. For example, we set out to grow six as a reaction to Brexit and the European Union’s unexpected prohibition on UK stock which meant we could not bring seed into England and Wales. There was always a voluntary ban on third country seed coming into Scotland as a means of disease prevention.

What success did you have?

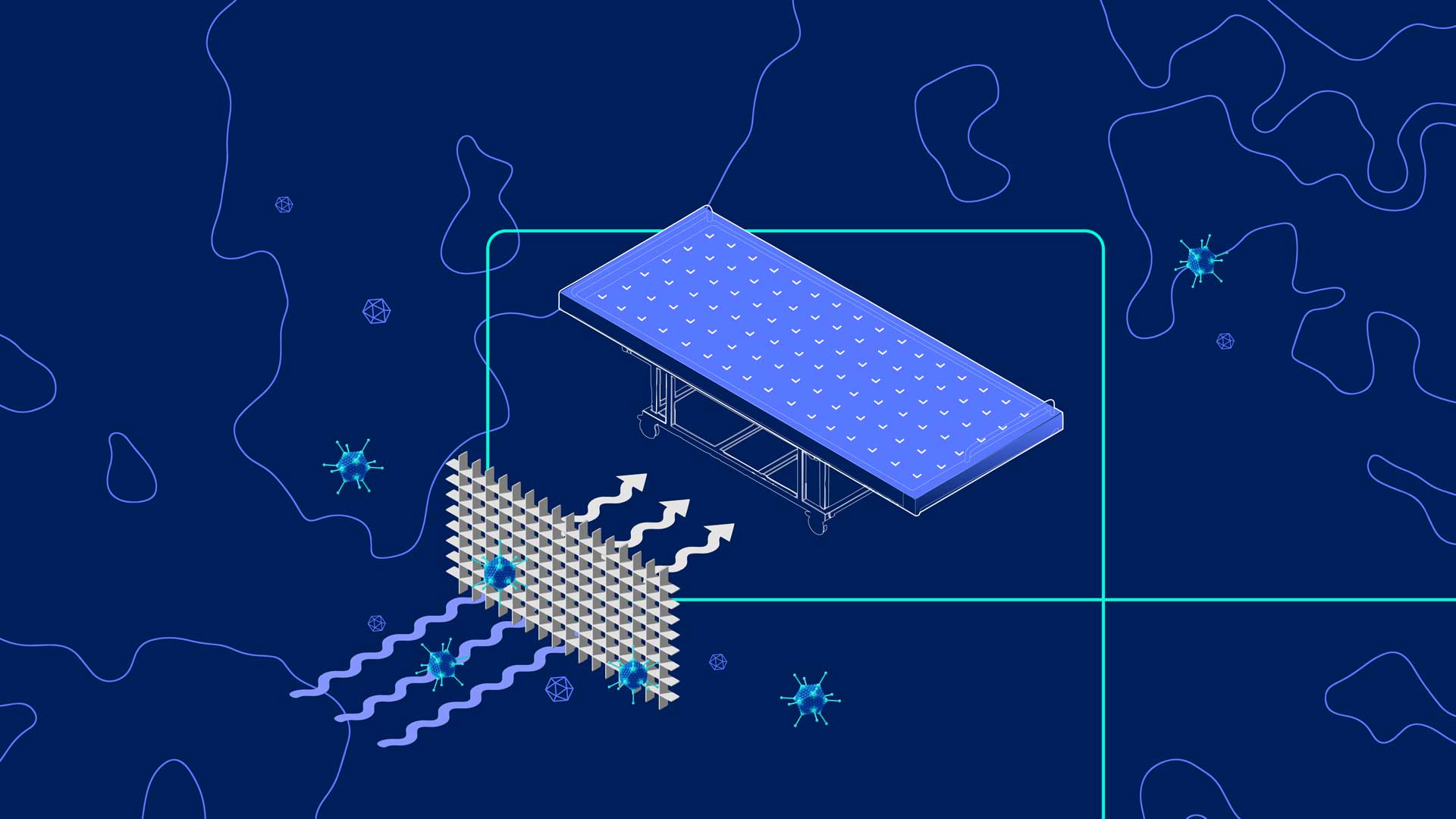

We recognised that we could perhaps accelerate development of some of the newer varieties with their excellent blight resistance or a nematode resistance. Nothing ventured, nothing gained! We agreed a programme and decided we would plant some tissue we received from SASA. We then moved these plantlets into the IGS Growth Tower. We had to double space the Growth Trays with Lights (GTLs) because the potato plant grows quite tall: you need head space, you need to leave space for water, room for the light to get through.

We planted our six varieties in the trays in the Tower and grew them for 90 days, replicating the nutrition and light levels that they receive in the field. Five of the six grew well, one didn’t much like the conditions: it’s an older variety that is still produced and multiplied here in Scotland and is a shy breeder that doesn’t tend to throw many tubers. This makes it quite tricky for the farmer in the field, but it proved that it didn’t like the tower either. The other varieties, however, did produce in some cases very satisfactory numbers of tubers. One variety – a newer one called Jacky, which is a salad type variety that can produce at field scale level up to 2.2 million tubers per hectare – did particularly well.

Following the 90 days, we harvested the crop back in March 2021, and brought it back to our store at Castleton to give it an artificial autumn and winter. By putting the crop into a cold store, the tubers naturally go into hibernation before we tried how they got on growing in a field.

The Jacky variety did extremely well and produced lots of stems and tubers in the field. Of the remaining five, four did well and one was again poor. While four out the five worked well, we did find that four of the five also wanted a longer dormancy period before they were asked to wake up again: they wanted to have a longer winter to rest to get their strength up.

What have you learned or discovered?

We are now at the stage where the crop has been chopped down, killed off to stop it carrying on growing by removing the top of the plant. We will harvest as many as we possibly can from these different varieties and replant them again from 2022: I think that will be the ultimate test for how successful the experiment has been.

We have already learned a lot about what sort of varieties actually might work and which varieties might not as they don’t suit that sort of environment. We’ve also been able to look at what happens if you rush them out to the field after starting off in a Growth Tower. It has been a really useful learning exercise on both our parts.

Potatoes are one of the most versatile food sources: in global terms they are the third or fourth most important food crop. There are 14,000 hectares of potato production in Scotland alone, which compared to cereals is nothing, however it is a very significant crop.

How important is collaboration across the public, private and academic sectors to move forward the agricultural ecosystem?

Up to 90% of food comes from plants and it’s clear that we are not going to have another ice age anytime soon, so no opportunity for a massive shake up of all our soils. We therefore have to get better at looking after them. It’s not necessarily about a sudden rush to organic, although there’s a place for that of course. The key thing for the future in my opinion is that we are at a time of change and opportunity within the industry. We are led by some very able people, but we need to hand on to the next generation. The way to do that, as I see it, requires strong links with innovative companies. And it needs even stronger links with private research establishments. Farming can only thrive if we embrace these sorts of academic sectors and the research sectors and the indeed the practical people who provide advice on the ground and we all need to work together.