Urban agriculture is frequently touted as the solution to many global problems, but does it make economic – or even environmental – sense?

IGS’ Offer Manager, Chris Lloyd, debunks common myths around urban agriculture, looking at where it is actually feasible, and how vertical farming could fit in. He explores how growers can profit from vertical farming technology, enabling market growth through innovation.

Urban agriculture is becoming an increasingly trendy buzzword. It often pops up in forward-thinking documentaries, pitching vibrant rooftop farms adorning city skylines. It’s seen as futuristic, but the practice actually dates back to the Mesopotamians, who would farm within large urban settlements all the way back in 3,500 BC.

The concept was also used in more recent times, when citizens were encouraged to grow their own food during World War II. Fruit and veg patches popped up across urban and suburban settlements in an effort to make nations more self-sufficient, as well as feeding into a spirit of collective endeavor.

Doing it at scale, however, comes with many challenges (many of which are often overlooked for the sake of pushing a narrative). Let’s look at where the concept makes most sense, and where vertical farming can step in to help meet market demand. First off, though, let’s explore traditional models of farming, as well as their relationship with urban farms.

The relationship between traditional and urban farming

Traditional, open-field farming typically takes place in rural areas where land is plentiful (not to mention cheaper than in cities). It benefited greatly from the Green Revolution and technological advancements in agriculture and, as such, humanity has benefited in tandem. Famine is now a thankfully rare tragedy – in many countries, death and disease from excess food (or the wrong type) is far more common than from a lack of it.

In a previous blog, I explored the importance of population-wide access to healthy, nutritious produce. While it may be possible to survive on a diet of mostly carbohydrate-heavy foods (like cereals and potatoes, which can be classed as commodity crops), any good diet contains a wide variety of crops that are perishable and non-commodity. Unfortunately, these are often imported from halfway across the world.

They demand a premium over commodity crops due to a shorter shelf life and protracted supply chain, not to mention the challenges which come with growing them in many climates. Yet in an ever-more health conscious (and increasingly urban) society, they’re in high demand. This has led to the concept of urban farming being seen as a possible solution, growing popular fresh produce closer to the consumer.

What makes sense to grow in an urban area?

Many countries import commodity crops (like grains and potatoes), whether by choice or necessity. This is often due to the inherently higher costs of growing domestically. In economic terms, smaller outdoor farms simply can’t compete with gigantic international corporations who monocrop farm these at a huge scale.

This only gets more complicated (and expensive) when growing in an urban setting. Land and labour are both perennially more expensive in cities, while there are more stringent planning restrictions in place (and that’s before you even get to the logistics of packing and distribution). Despite their abundant nature, these factors mean it just doesn’t make sense to grow commodity crops in an urban area – at least for now. But what about non-commodity crops?

Growing to consumer demand

Consumers have demonstrated that they are willing to pay for quality. Crops labelled organic, Fairtrade, locally sourced, or non-GMO are ever-popular, despite often commanding a higher price tag. This could be anything from green, leafy crops like kale and spinach, to salad-fillers like rocket, lettuce, right through to tomatoes and niche products like edible flowers and microgreens. Many of these crops are imported depending on the season. Freshness is paramount (after all, who wants a soft tomato or wilted bag of spinach?), and growing these crops at scale throughout the year can be challenging when using traditional methods.

%2520(1).webp)

This is where the concept of urban farming starts to make sense. Here at IGS, we see the main benefits of growing in urban areas as:

- the ability to grow crops year-round: there are very few countries where crops can be grown traditionally 365 days a year outside (largely due to weather constraints). Domestic demand tends to be constant (and diets don’t take seasonality into account), so this is where it makes sense to look at other growing operations

- increased shelf life: growing food closer to the consumer means that they can get access to fresher produce. This means that businesses can charge more, whilst reducing the need for harmful chemicals which can artificially alter or extend shelf life

- reduced imports: it’s counterproductive to geopolitical goals to be overly reliant on other countries for imported produce , while the environmental benefits of taking out carbon-heavy food miles are sizeable (at present, global food miles account for nearly 20% of all food-generated emissions)

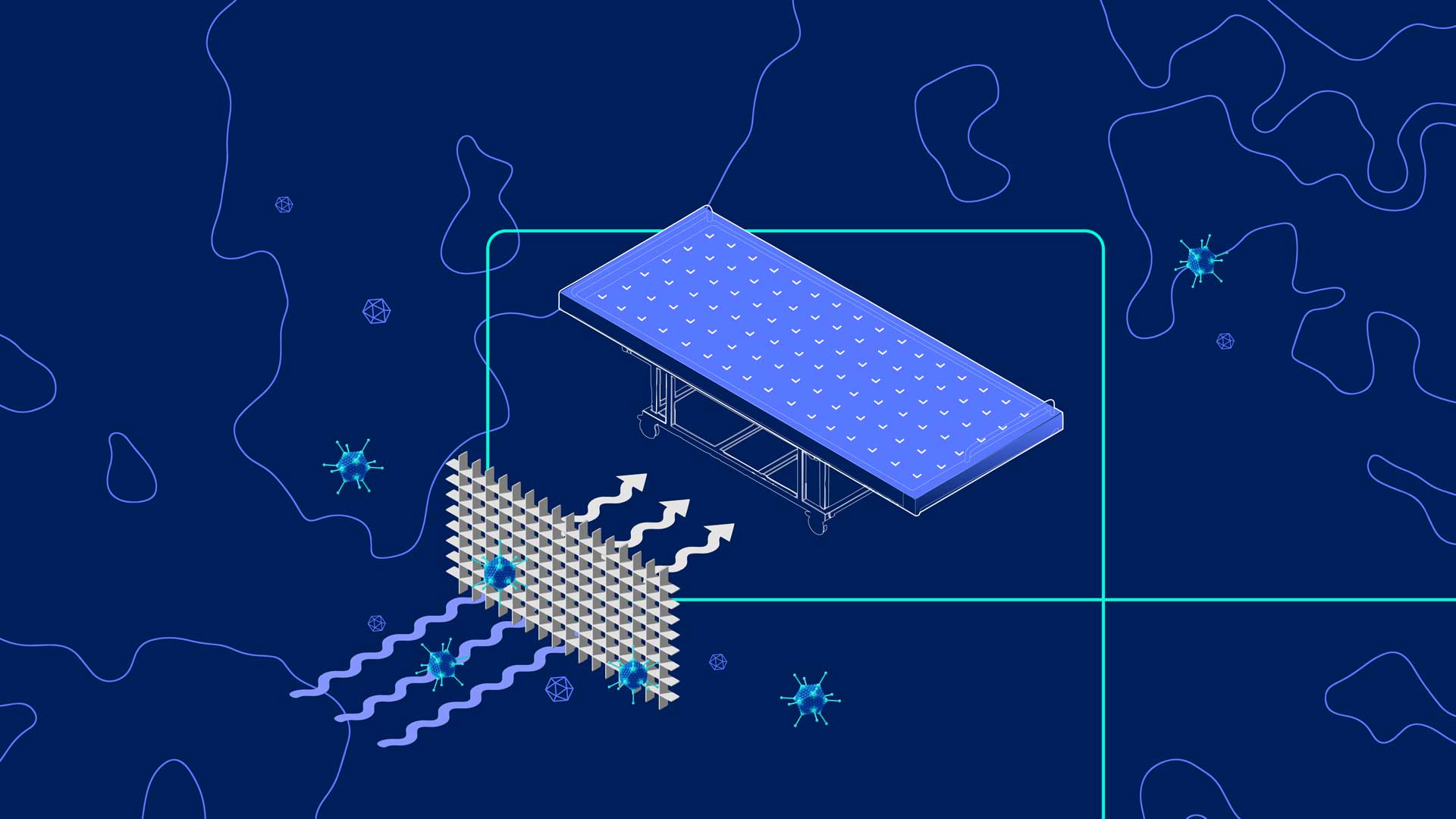

- growing crops which would be challenging to grow traditionally: certain agricultural sectors are under existential threat from extreme weather, pathogens decimating traditional production, or simply reaching the limits of what can be grown using our planet’s natural resources. We believe in looking beyond traditional agriculture to help breathe new life into these areas

Any successful business is built off a solid backbone of research. Speak to offtakers and figure out what the market demand is, then investigate what could be sourced locally at a viable price. Certain crops (particularly those that can be grown in a vertical farm) make far more economic sense than others. At IGS, we’re happy to support you on this journey through profitable, sustainable, and innovative technological solutions.

Where does it make economic sense to build a farm?

An elephant in the room when it comes to the idea of urban farming is the supply chain. Growing salad leaves in the same city that they’re going to be consumed sounds like a no-brainer, until you start to consider the process involved in getting these leaves from farm to fork. Existing supply chains are geared towards rural farms.

Everything from packaging and distribution, to sorting, grading and processing food all takes place outside of city centres (often in ports to be processed before and after shipping). Growing produce in these areas is known as ‘peri-urban agriculture’. It would be entirely counterproductive if an urban farm had to ship its produce back to rural areas, then back to the city for the consumer, so we need to look at where makes the most sense to host the entire food production process.

Land in peri-urban areas tends to be cheaper and in less demand than the city centre, making it the perfect site for a so-called ‘urban’ farm. By locating the farm here, any transportation costs between the harvesting crops and packaging are effectively eliminated, bringing both financial and environmental benefits. These areas also make optimal locations for power generation. A ‘GigaFarm’-scale vertical farm, for example, could take advantage of the lower energy prices offered for direct-electricity connection by collocating next to the point of energy generation.

Although the concept of ‘urban farming’ may initially seem suited to real estate in sprawling metropolises, the reality is somewhat different. If you want to grow profitably at scale, with access to all the required packaging and processing, then it’s vital to locate close to these facilities – or have space to host these facilities at your vertical farm.

The scale of packaging and distribution facilities presents another problem, particularly when you factor in expensive real estate (typical in most cities). Even with dozens of layers in your vertical farm, it’s hard to achieve a high enough profit to justify locating on prime urban real estate. The real benefit comes when looking at locations that aren’t desired for other uses (and as such have a lower price tag), such as brownfield or greyfield.

How can vertical farming fix the puzzle?

Co-locating supply chain facilities with a vertical farm is a model that works well. Growers aren’t restricted to seasonality, and can grow typically out-of-season crops regardless of the time of year. Vertical farms can also be powered by 100% renewable energy. This opens up opportunities for businesses to co-locate with renewable energy providers, potentially making significant cost savings (and increasing green benefits).

At IGS, our technology is built on resource efficiency. Our Growth Towers use up to 73% less water than greenhouse operations, and up to 98% less than open field farming. This allows growers to appeal to a more environmentally conscious audience, as well as getting the most out of every drop of resource.

So, should we grow urban?

It’s clear to see why cities are not completely self-sufficient with urban farms, and why they very likely never will be. Growing food in and around cities should be part of a wider solution, but for now it remains limited in scope to non-commodity, often imported, difficult-to-source crops. We believe that a more significant impact can be made by growing crops in larger GigaFarm-scale facilities, capable of making a significant contribution to a nation or city’s food security.

We’re always happy to speak about what makes sense to grow vertically. Whether you’re looking to grow nursery plants, seed-to-harvest, or something entirely different, we can help you see whether vertical farming could fit into your operations.

Get in touch to find out more.

.jpg)